Finding a place to take a stand

Mapping regions bio and cultural

11 minute read

Regions in a time of breakdown

The Raven is increasingly focusing on the concept of regionalism, the idea that, as urbanist Lewis Mumford put forward many years ago, there is a “regional framework of civilization.”

Mumford’s thinking, to which The Raven devoted a series beginning here, is that regions are the basic units through which the world is connected. He wrote, “Real interests, real functions, real intercourse flow across (national boundaries): while the effective organs of concentration are not national states . . . but the regional city and the region.”

This is more than an abstract discussion. In focusing on the regional dimension, I am pointing in a direction to cope with and eventually rebuild from a time of national and global breakdown. As the tagline of this web journal states, to plot a path for “living beyond empire.”

Breakdown is increasingly in the foreground. Conflicts and divisions are growing within nations and between them. Supply chains are snapping. Climate chaos is intensifying. National and global institutions are increasingly incapable of responding to the interwoven crises facing us. In fact, national and global elites continue to pursue models through which they have gained power and wealth, even as the destructive consequences of those models escalate. Whether it is continuing to expand the production of fossil fuels and arms, or perpetuating a profit-oriented capitalism heedless of social and ecological impacts.

Elites insulated in their bubbles will be the last ones to feel the consequences, which is why they will continue to prolong them. As historian Arnold Toynbee determined from his study of civilizations, this is the dynamic that causes civilizations to collapse.

The torrent of daily bad news, seemingly on all fronts, is driving many to despair. This is completely understandable. I struggle with grief myself over what is being lost, as I wrote about here. But we don’t have an option to give up, not if we want to leave a world with which our children can cope. We will be in struggle in coming years with the many dark forces coming upon our world, with institutions sunk in corruption, with ideologies that twist people’s minds. We need to find a common ground on which to struggle, and rebuild from the breakdowns which are now inevitable. We need a place to make a stand, a home ground. That place is the region.

Defining the region: The bioregion

Region is an ambiguous term, capable of describing geographies on many levels up to continents and large sections of continents. Region in the context The Raven uses it is bounded closer to home, more centered around coherent natural and cultural unities. But ambiguities remain, because those realities do not necessarily overlap. This is a reason for my use of the broader term, regionalism. It reflects the realities of culture as it exists on the ground, as well as the bioregional aspiration to build cultures more in tune with nature.

There is a bioregional reality drawing from the natural features of a region, predominantly in how the waters flow. Water is the fundamental element of the biosphere. It makes up 60% of the human body, and is the foundation of plant and animal life. The nature of a region is strongly conditioned by how much or little water it receives.

A great deal of climate disruption centers around the water cycle, how skewing key global wind circulation patterns such as the jet stream brings droughts to some places while drenching others. A place that one year is under a searing heat dome may be hit by record rainfall the next (exactly as we have experienced in the Cascadia bioregion between 2021 and 2022.) Wildfires, crop failures and floods are the outcomes. As we adapt to inevitable climate changes, how we use and live with water will be a core concern. That necessarily will draw the issue close to home, to the bioregions in which we live.

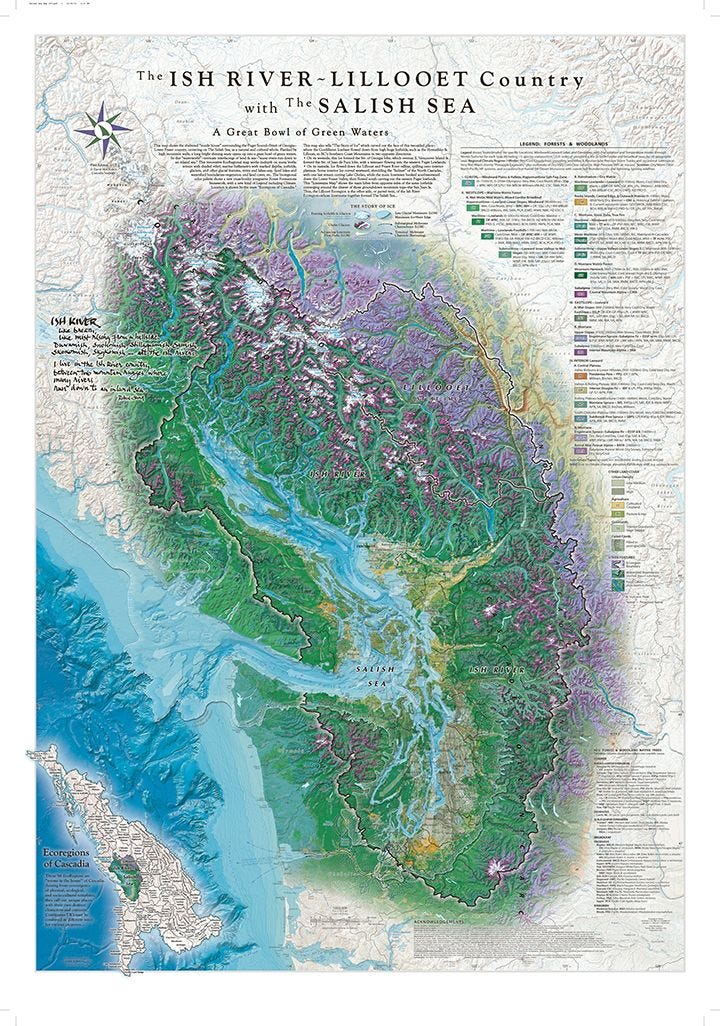

I lead off this post with David McCloskey’s recent Ish River-Lillooet map, based on the natural unities around the Salish Sea and associated watersheds from mountain crests to the coast. It is a wet country, with some of the highest rainfall levels in the world. Mountain ranges catch storms blowing in from the North Pacific to feed some of the thickest forests on Earth and rivers running with salmon. Ish River-Lillooet is, in the lingo of bioregionalism, a combination of closely connected subunits known as ecoregions, also mapped by McCloskey, a retired Seattle University sociologist who is a progenitor of the now widespread Cascadia idea, which I detailed in my recent piece on the Pacific Republic.

The cultural regions of Cascadia

Living in Cascadia, aka the Pacific Northwest, I am acutely aware of a cultural boundary roughly running along the crest of the Cascades Mountains. Also known as the Cascade Curtain, it may be one of the starkest dividing lines on the continent. Cascadia has a natural unity in the flows of the Columbia-Snake and associated coastal watersheds, but politically and culturally it is two different places. To the west are some of the most liberal-lefty cities and towns in North America, while to the east are some of the most conservative areas, at least on the U.S. side of the border. It’s not a pure division. Rural areas on the westside also tend to be conservative. But the west, unlike the east, is urban dominated.

The original settlers of Seattle and Portland hailed from New York and Boston, and came by ship. In fact, Seattle’s original name was New York Alki, the native word for by-and-by. Portland’s name was selected by a coin flip between two merchants. The Portland, Maine native won. In the 1970s, an underground paper called Almost Boston was published in Portland. The westside has many resonances with the Northeast.

In contrast to the cities, the original white settlement in rural areas came by land, down the Oregon Trail from places such as Missouri, Kentucky and Tennessee. That was reinforced by a large flow of Arkies and Okies during The Grapes of Wrath 1930s depression era. They formed a great deal of farm labor in that era. The areas east of the mountains have a distinctly different feel. I have the benefit of having lived on both sides. As a county beat reporter writing for newspapers in Eastern Washington in my late 20s, I covered agriculture and events such as the annual rodeo. I lived most of the ‘80s and ‘90s in Portland, and in Seattle since. I like to say that in Cascadia, to go west you have to drive east across the mountains.

Mapping cultural divides

The east-west divide is reflected in broader mappings. Take this one drawn by Colin Woodward for his 2011 book, American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America. Woodward’s nations curl around in some pretty strange ways. You would have a hard time assembling coherent political units out of them. But they are based on detailed demographic studies that reflect the patterns of white settlement across the continent.

Because Woodward’s map is based on demography, he does do a better job of illuminating cultural realities than Joel Garreau did in his 1981 work, The Nine Nations of North America. Nonetheless, the two mappings have some remarkable resonances, particularly in the west.

In both mappings, boundaries between west and east along the mountain crests emerge in sharp clarity. Interestingly, both stretch the cultural region west of the mountains down to the San Francisco Bay area. Some maps of “Big Cascadia” have done the same.

Bringing it closer to home

In my region, cultural divisions between west and east make it difficult to envision a common political response to coming breakdowns. While the bioregion is a natural reality, cultural realities prevail in politics. Thus, I believe, we must orient to ecoregional realities closer to home, which are more aligned with cultural realities.

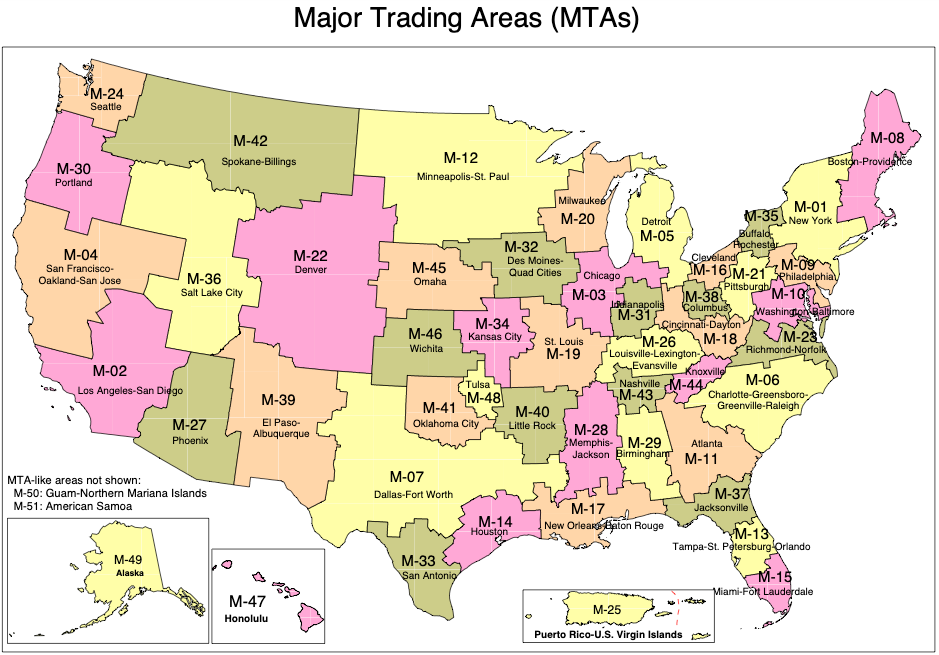

That shows in maps of metropolitan trading areas. This map from the Federal Communications Commission, which uses it to assign wireless frequencies, is based on the 1992 Rand McNally Commercial Atlas and Marketing Guide. It still seems to fit existing cultural and economic flows around metropolitan areas. In the 1988 edition Rand McNally says, “The boundaries have been determined after an intensive study of such factors as physiography, population distribution, newspaper circulation, economic activities, highway facilities, railroad service, suburban transportation, and field reports of experienced sales analysts.”

This map shows a more complex reality than the broader cultural mappings. The economic reach of major west coast metropolitan areas extends well east of the mountains. This rings true to my experience. In my time as a county beat reporter, I lived in Okanogan County which was bounded on the west by the Cascade Crest. The county was clearly oriented to Seattle. When you went to the city, you drove across the mountains. (Whole areas in Okanogan and other east slope counties have aspects of being Microsoft nature preserves, with large swathes of land purchased by stock option vestees.) Earlier, I lived east of the line in Grant County. There, you drove over to Spokane if you wanted to buy a major item, or just get a taste of urbanity. Spokane actually has some pretty good restaurants and bookstores.

Other places in my experience also resonate. Living in Portland, it was clear the counties to the north oriented to the city south of the Columbia. I grew up near Philly toward central Pennsylvania, and here the mapping also feels quite accurate.

These mappings of metropolitan trading areas strike me as being the closest to “really existing” cultural realities, and the city regions described by Mumford. If you juxtapose them with the ecoregions mapped above, these is a close but not perfect contiguity. For example, compare the mapping of the Willamette and surrounding ecoregions with the Portland metropolitan trading area, or the Ish River and surrounding ecoregions with the Seattle trading area. As we assemble responses to emerging crises, this juxtaposition of ecoregions and metropolitan trading areas seems to map the natural scale at which to assemble coherent political and economic responses.

A studied ambiguity

In ecology, an ecotone is a transition zone between biological communities. It is neither one or the other, but a mix of both. In terms of culture and politics, we also need to think in terms of ecotones, crosshatchings where powers and identities are shared. Things don’t have to be all one thing or another. They can be both.

“ . . . all boundaries in black and white are, in one degree or another, arbitrary,” Mumford wrote in his classic, The Culture of Cities. “Reality implies a certain looseness and vagueness . . . To define human areas, one must seek, not the periphery alone but the center . . . The region, no less than the city, is a collective work of art.” We define the region not only by physical geography, but by our own actions.

Political breakdown is increasingly coming to the fore across the world. In the U.S., political camps are increasingly at each other’s throats. Secession movements emerge from both the right and left, from Texas to California. Rulings by a radical right Supreme Court on issues ranging from guns and abortion to climate are bound to draw distinctions and tensions between red and blue states ever more sharply. At the national level, we cannot expect coherent political responses to the crises growing all around us. To do that, we are going to have to build new common ground in places closer to home, in communities and regions.

Today we are cursed with the concept of the nation-state sanctified by the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia, ending wars of 80 years. One distinct people in one bounded state. Countless wars have been fought and are being fought to define hard boundaries. In confronting a changing world, we need to shape new political forms that more mimic and reflect ecosystems, with their diversity and often ambiguous boundaries. We are going to have to build regional polities from centers out to peripheries, linking with neighboring regions through transition zones, ecotones where we join to build common responses.

In struggling for the future, we need a place to take our stand, a home ground. We will find those places in the regions where we live, drawing the boundaries loosely, and building common ground between us.

This article was originally published in The Raven. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to The Raven, even though (rather generously) you can read it for free. Patrick does need to eat and pay other basic living expenses.